The Red Ensign is a publication dedicated to Anglo-Canadian people, their history, and to all that they could be again. For both of these purposes we frequently publish pieces reviewing the lives of the great men of Canada’s history, highlighting the elements of their lives that an elite prepared to lead this people into the future should seek to embody. Donald Alexander Smith, later known as “The Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal” was a self-made aristocrat of the Colonial era of British North America. In his work he embodied the fortitude, vigour, aspiration, and noblesse oblige of the Anglo-Canadian elite of the era; a generation of men who carved a great nation out of frozen and empty wilderness. His story, like many of those profiled here, draws a sharp contrast with the lesser and meaner elites that dominate Canada’s current political landscape and reminds us of who and what we can be, as a people.

Smith was, like many colonials, the second son of an unremarkable Scotsman of aristocratic birth; his grandfather was Donald Stuart, descended from the 2nd Duke of Albany. After an unremarkable education and an apprenticeship at the law offices of Robert Watson in Forres, Scotland, he accepted a junior clerkship in Montreal in the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company offered through the influence of his uncle John Stuart, who had been a partner in the North West Company before becoming a Chief Factor (a kind of local partner operating an assigned territory with an assigned profit share) for the Hudson’s Bay Company after it absorbed the NWC.

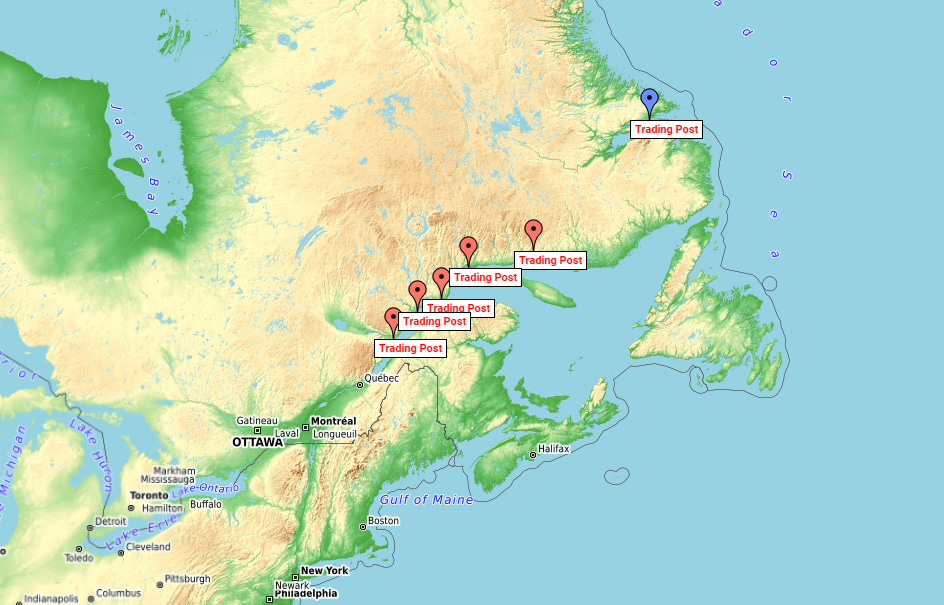

Smith stayed briefly in Montreal, where he met George Simpson, the Governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company by way of a letter of introduction from his uncle. After an interlude in which Smith was alleged to have attempted to become too familiar with Simpson’s wife, Smith was then assigned to a series of trading posts up and down the Gulf of St Laurence. After seven years of working these trading posts, and a continued troubled relationship with Simpson, Smith was reassigned to the Labrador region. After a brief contest with existing Labrador management, Smith was elevated to Chief Trader of the post and would spend the next 20 years diversifying the business of the trading post to include a salmon fishery, seal harvest, and mineral exploration. In 1869 he was promoted to Chief Factor of the Montreal District, which also included responsibility for all the posts of the St Lawrence, Ottawa, and Mattawa River.

Smith returned to Montreal, the center of Canadian political life at the time, shortly after the reorganization of the Colony in 1867, and the surrender of the former territories of HBC to the new Dominion Government. By this time the first political crisis of the new Dominion was well underway; the new Dominion government, in preparation for settlement of the west, had attempted to re-survey the farmland of the Red-River colony, located in what is now southern Manitoba, in preparation for the anticipated Anglo-Protestant settlers and later the railway. The clumsy effort led to armed rebellion among the Metis [Franco-Catholic/Native] settlers in the region. On the recommendation of George Stephen, Smith’s cousin, and close associate of Prime Minister Macdonald, Smith was sent to the colony and successfully negotiated terms for incorporating the colony into the Canadian Confederation. Smith was so abundantly successful in winning the confidence of the colonists that he was then elected to represent them in both their new provincial legislature and the House of Commons in 1870 & 1871 respectively until 1878.

In the period between 1865 and 1869, Smith and his cousin George Stephen had a productive business partnership; Stephen introduced Smith to lucrative investment opportunities in the Montreal business community and Smith leveraged his influence with the Hudson’s Bay Company to serve as a distributor for the textile products of Stephen’s mills. In 1871, after his successful resolution of the Red River Rebellion, Smith successfully negotiated the compensation package to cut HBC’s Chief Traders and Factors out of the profits of future land development deals the company might make, was promoted to chief commissioner of the company to cut himself into those profits, and leveraged his position in Manitoba politics to ensure those profits were made.

In 1874 Smith, again leveraged his relationship with George Stephen, now a director for the Bank of Montreal, to lead a syndicate of investors to buy assets out of bankruptcy from the St. Paul and Pacific Railway; with the freshly injected capital, construction was completed northward to connect it to the Canadian line 1878, operating it as the highly profitable St. Paul, Minneapolis, and Manitoba Railway.

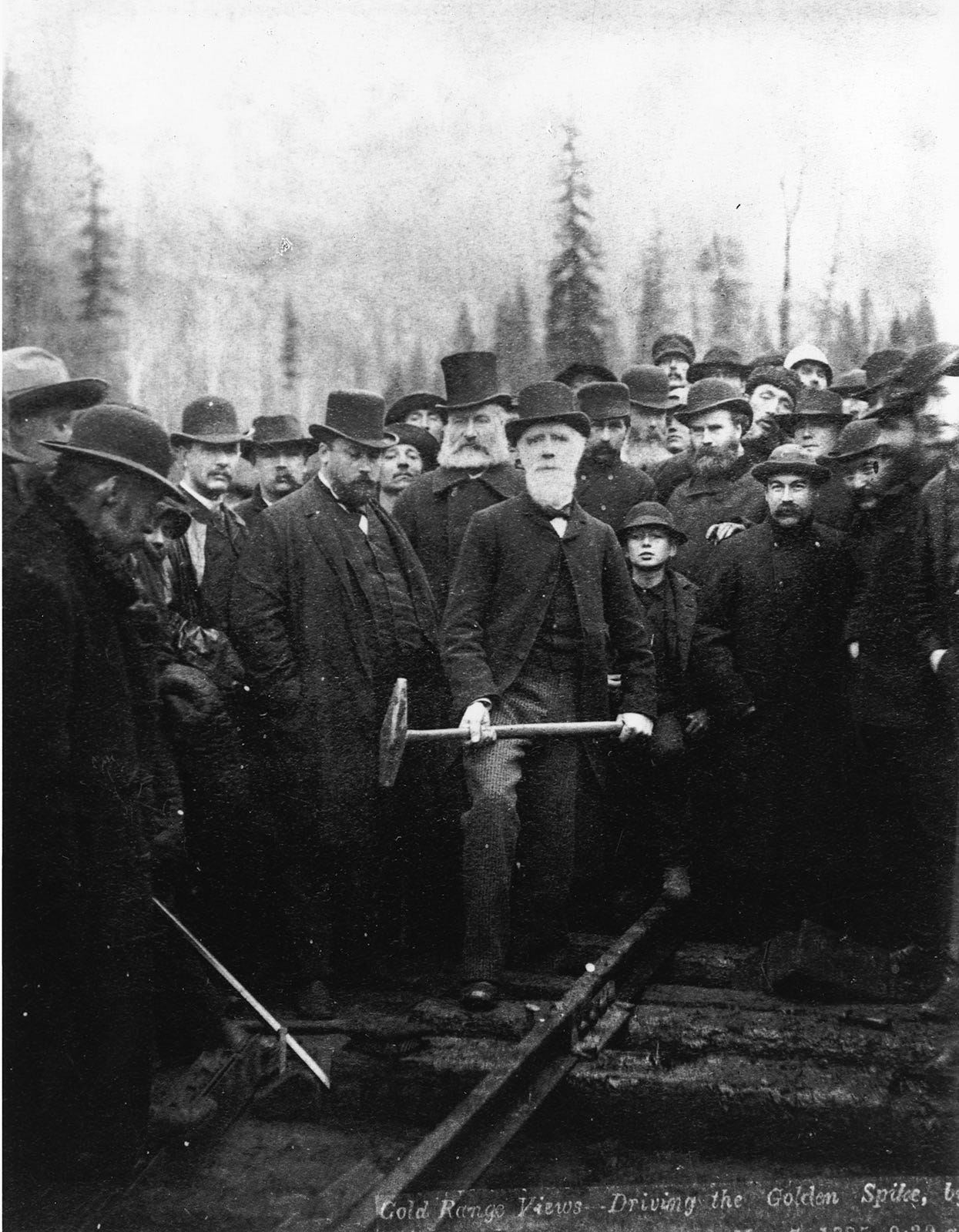

In 1873 a political crisis occurred within the Conservative government led by PM John A. Macdonald over an arrangement between Macdonald and other senior figures in the Conservative government and shipping magnate Hugh Allen, in which Allen contributed campaign funds in exchange for the contract to build the then-proposed trans-continental railway. Smith was not involved in the scandal, and was one of several Conservative MPs to leave the party and end Macdonald’s term as Prime Minister, as well as Allen’s efforts to build the railway. In 1878, when Macdonald’s Conservatives returned to power, the railway contract was awarded to a syndicate of investors led by Smith, Stephens, and JJ Hill. Smith was also the principal shareholder in the Toronto, Grey and Bruce, Credit Valley, Ontario and Quebec, and the New Brunswick railways, all of which would be purchased by the newly formed CP Railway to complete the transcontinental link. In 1880 Smith became a director of CP Railway, and would have the honor of driving the last spike of the transcontinental line.

Smith leveraged his personal financial success in the railway and real-estate businesses to purchase controlling interests in the key nodes of corporate power that produced that financial success. By 1890 he was the principal shareholder and president of the Bank of Montreal and The Hudson's Bay Company, as well as a key shareholder and Board of Directors member of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

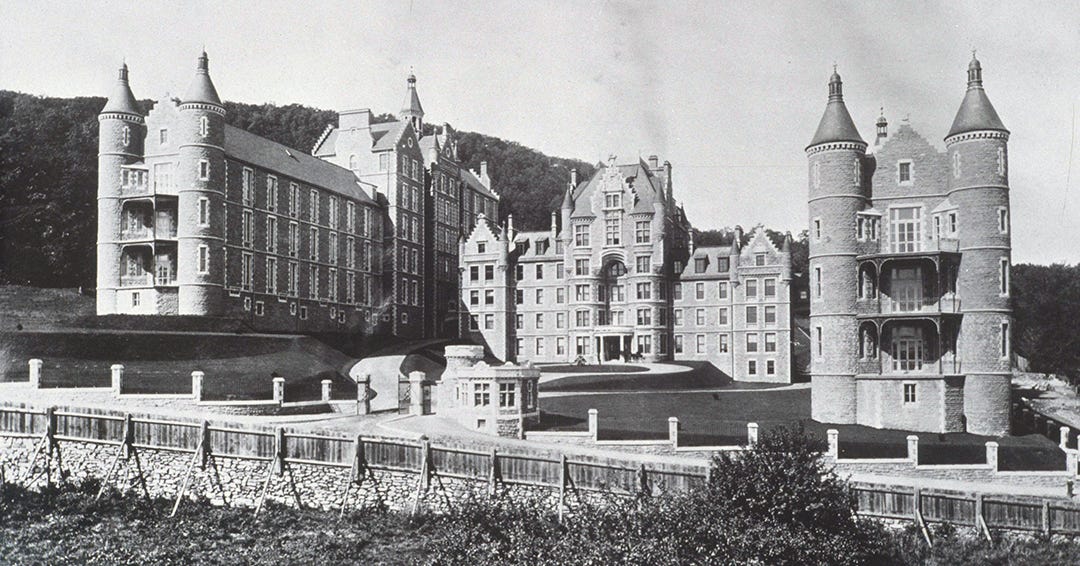

In 1885 Smith turned 65 years of age, the last spike of the CP railroad had been driven, metaphorically closing in success the twofold project of personal financial success, and in the building of Canada. Smith dedicated much of the rest of his life to leveraging his personal success into building a heritage for the Colony & Empire that he loved. In 1884 Smith began his association with McGill University, where he would serve as chancellor as well as financing the founding of Royal Victoria College, and Royal Victoria [Teaching] Hospital. He also served as Lord Rector of the University of Aberdeen in Scotland from 1897 to 1900 and made significant contributions there.

In 1887 Smith re-entered official politics as an MP for Montreal West, sitting as an “Independent Conservative”. Even without a formal seat in the Conservative Party, Smith declined the offer of Mackenzie Bowell to succeed him as Prime Minister after the sudden death of John Thompson in 1896. Instead, he assumed the role of HBC Governor and High Commissioner for Canada in London, posts he would retain until his death in 1914. In 1897 he was made a peer, and took the title First Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal. In 1900, after the outbreak of the South African war, Smith was a strong advocate for colonial participation in the Imperial project and therefore the war. After failing to broker an agreement for direct participation of the colonial government, he offered to raise and equip & transport a regiment at his own expense. The regiment, known as Lord Strathcona’s Horse was 600 strong and served with honor in the conflict, at an estimated cost of more than $1 million. Smith would remain an avid patron of Imperial armed forces for the remainder of his life, serving as an Honorary Colonel of the 8th Battalion, Liverpool Regiment, from 1902 onward, and being instrumental in the founding of the Royal Canadian Army Cadets in 1910.

Smith lived an astounding life. In his strength, endurance, and acumen representing the Hudson’s Bay Company across the great northern hinterland; In his ambition and fortitude transforming the western frontier politically and materially; In his commitment to the Canadian people and the wider commonwealth; Donald Alexander Smith embodied both the best of the Canadian people, and a truly great aristocrat. His memory should be an inspiration to our people, a reminder of all that we were, and could be again, in a world changed. The Red Ensign would like to encourage our readers to reflect on what it would look like for a modern elite in Canada to embody these virtues again, and to consider anew what it would mean for us to become a great people again.

Sources/Further Reading:

HBC Heritage — Donald A. Smith

Connecting Canada (CP Rail Archieve)

Lord Strathcona also set aside $100K in 1910 to fund the Army Cadet organisation. They award the Strathcona medal every year to a deserving cadet.

You don't see that kind of old school aristocratic philanthropy anymore. Except for maybe Jimmy Pattison donating hundreds of millions for hospital wings, clinics and Christian schools. But Pattison came from very humble beginnings, so not true old money per se.